For many, the concept of a rock star is synonymous with a very specific image of masculinity. But throughout the history of popular music, that image of masculinity has been moulded — sometimes in line with societal norms, sometimes at odds with it. Here, we look at some examples of how various musicians have reshaped masculinity for themselves.

The 19th of November is International Men’s day. The contribution of men to popular music is hardly worth stating, being based on the same patriarchal structures that defined much of the century in which popular music was born. But throughout the development of this music, numerous individuals challenged the toxic masculine traits of violent behaviour, aggressive hetrosexuality, and emotional ignorance.

We are lucky to live in an age when changing gender norms means it is easier to discuss what it means to be a man. However, expectations are still present. People still talk about being a “real man,” boys are still mocked and bullied for being too “sensitive,” and men are still three time more likely to die by suicide than women. Suicide is the most common cause of death for men under 50, and men are more likely to suffer drug and alcohol dependence and to be sleeping rough.

Yet transgressing traditional views of masculinity is as old as show business itself. From the submissive weak clown to the drag artist, the stage has been a refuge of make-believe, where men can escape societal expectations.

But the image of the rock’n’roll star, one of the 20th century’s most enduring icons, is one still drenched in hegemonic and toxic masculinity. Rock history is full of the image of the powerful musician, sexually confident and untouchable, claiming multiple “conquests” and smashing up hotel rooms. Yet many of the earliest inventors of the art form did not conform to this stereotype.

Good golly, Miss Molly

Little Richard

Little Richard was born in Georgia in 1932. As a child, he had a smaller frame than many of the boys his age, leading to his moniker. He was often mocked due to his “effeminate walk and mannerisms” and was often beaten by his father when caught trying on makeup and women’s wigs, eventually being thrown out of the house for being gay, according to Richard. In his 20s, Richard performed as a drag artist, but it was in the rock’n’roll boom of the 1950s that Richard really made his name, with hit singles such as Tutti Fruiti and Long Tall Sally.

Richard’s stage performances were energetic and flamboyant, and he wore wigs, face powder, eyeliner, and other makeup. Though his music was driving and aggressive, with sexually charged, hetronormative lyrics, his effeminate look had white audiences labelling him a “sissy” and considering him sexually nonthreatening to white women. Thus, he was allowed to play to mixed, white and Black audiences, helping him become one of the earliest crossover stars.

He told the magazine Jet in 2000, “I wore the makeup so that white men wouldn’t think I was after the white girls. It made things easier for me, plus it was colourful, too. I figure if being called a sissy would make me famous, let them say what they want to.”

In reality, Richard’s sexuality was complex and full of contradictions. He was both sexually promiscuous and pious, rejecting homosexuality as against church teachings. However, his impact on early rock’n’roll, introducing gender ambiguity in a world dominated by aggressively macho characters like Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis, along with his sheer talent, led him to be called the “Architect of Rock’n’Roll”.

My generation

As rock took hold of youth culture, its songs reflected the changing nature of youth. In the affluent post-war years, teenagers and young adults had greater disposable incomes and more free time.

A mod

In the U.K., mod culture saw young, working-class men embrace high fashion in a way their manual labourer fathers had never considered. British scene bands such as Small Faces, The Creation, and The Who both followed and led sartorial trends that included long trips to hairdressers and clothing shops, behaviours typically associated with affluent women. Some of the more daring men even wore eyeliner. As the 60s progressed, fashions became more flamboyant, as documented in The Kinks’s 1966 hit Dedicated Followers of Fashion. However, there were still the familiar strains of toxic masculine violence, as rival gangs of mods and rockers would engage in street fighting to establish dominance.

Wouldn’t it be nice?

In the U.S., pop songs were big business, and one of the most successful songwriters of the decade was Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. A string of hit singles and albums saw the band document the dominant youth culture of the day. Songs about surfing, dating, and fast cars connected well with an audience that had clearly defined roles for men and women.

Brian Wilson

However, beneath formulaic lyrics, Brian Wilson’s music was getting more complex. And with his sonic expansion, he wanted more diverse, mature, and nuanced lyrical content. Wilson was different from the boys depicted in the songs. He was afraid of the ocean, shy, and had severe stage fright at times. He was also frightened of his abusive father, who managed the band and would often drunkenly berate them.

In 1965, no longer touring, Wilson worked with lyricist Tony Asher on the album Pet Sounds. Musically, Pet Sounds was a leap forward, employing innovative recording and arrangement techniques that had scarcely been heard on a pop record. The lyrics conveyed an emotional nuance that was removed from the simplistic, macho bravado of earlier hits.

Lyrics such as such as “God only knows what I be without you” (God Only Knows), “I’m a little bit scared ’cause I haven’t been home in a long time” (That’s Not Me), and “Sometimes I feel very sad, I guess I wasn’t made for these times” (I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times), showed more introspection and emotional intelligence than was often found in pop music.

Despite eventual critical acclaim, Pet Sounds was not an immediate success in the U.S. when released in 1966. Its initial poor sales affected Wilson’s mental health, contributing to symptoms of schizoaffective disorder and depression that he experienced throughout the height of his career. However, the industry insisted that he present a clean, nonthreatening image. And, perhaps also influenced by a society that encourages men to deny, hide, and ignore emotional struggles and mental health conditions, Wilson refused counselling for years, opting to self-medicate with narcotics..

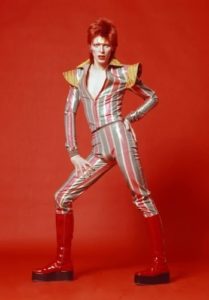

The man who sold the world

David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust

Toward the end of the 60s and in the early 70s, the “rock god” was a leading male paradigm of popular music. Though stadium rockers like Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones were flamboyant, their machismo remained. But as heavy rock morphed into glam rock, artists such as Elton John and David Bowie became famous for their sequinned costumes and onstage makeup.

David Bowie, in particular, played with gender norms in developing the androgynous character of Ziggy Stardust. As the women’s liberation movement gradually gained traction on the streets of Western Europe, and homosexuality was slowly being decriminalised, Bowie showcased a new way of being for men — neither gay nor straight, neither camp nor macho.

Though glam rock offered crumbs of opportunity for self-expression, it still demanded a facade. Major artists such as Freddy Mercury and Elton John remained secretive about their sexuality under pressure from, among other influences, a judgemental press that could accept and even celebrate rock star excess but not the idea of gay love.

Sexually ambiguous dressing would be picked up by heavy metal in the 80s, with men performing in high heels and makeup but still creating misogynistic lyrics and imagery.

You make me feel mighty real

Sylvester

In the mid-70s, away from the rock scene of loud guitars and thundering drums, where being someone other than a white hetro male was to be treated as an oddity, a small musical movement celebrated and encouraged groups whom society at large was still trying to marginalise.

The earliest disco clubs, as we now know them, were private parties in New York, such as David Mancuso’s The Loft. The privacy offered a safe space for gay and gender-queer males who were harassed by the police in public clubs.

The eventual disco clubs were mixed, and the high percentage of gay and Black punters offered even straight white men opportunities to strike up friendships with people whom they would scarcely have mixed with otherwise.

Like much of the audience, many of the music makers behind disco’s classic era were openly gay. Born Sylvester James, Jr. in L.A. in 1947, pop singer Sylvester was known for his flamboyant style and openness about his sexuality. The singer of hits like Dance (Disco Heat) and You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real), he wore both male and female clothing, started new fashions, and became an unofficial spokesperson for the gay community. He once told a journalist, “I realize that gay people have put me on a pedestal, and I love it. After all, of all the oppressed minorities, they just have to be the most oppressed. They have all the hassles of finding something or someone to identify with — and they chose me. I like being around gay people, and they’ve proven to be some of my closest friends and most loyal audiences.”

As disco hit the mainstream, it attracted wider audiences. The glitz and glamour of the clubs, the flashy fashions, and the dance trends became a hit, as the nightlife industry realised that it was cheaper and easier to employ DJs than hire live musicians. The disco craze hit its high point with the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, yet the protagonist was a far cry from the roots of the movement. John Travolta played Tony Manero, an aggressively hetrosexual male who approaches dancing as a competition, a way to assert dominance in an atmosphere of sexual competition and jealousy — the opposite of early disco’s pansexual attitude that offered community and respect.

Into the light

Viv Albertine of The Slits with Paul Simenon of the Clash

While disco slowly morphed from soul and psychedelia to capture the imagination of the 1970s, punk hit it like a brick. Though it’s hard to characterise such a diverse movement, the true meaning of which people still argue about today —for many young people of the desolate Britain of the late 1970s, punk provided an opportunity to reject any and all expectations. It was an escape from the drudgery of underpaid work or unemployment and a firm rebuttal of the impenetrable and patriarchal music industry championing progressive rock artists of the day.

In a popular culture still dominated by toxic lotharios such as James Bond and Mick Jagger, punk also offered a new, more positive way for people of different sexes to interact . Though many of punk’s biggest bands were male-dominated, an increasing number were female or mixed, such as Talking Heads, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and The Slits.

A scene that for many onlookers seemed antisocial was slowly encouraging more equal relationships. Women were no longer seen as just fans or sex objects, and people of different genders were working together, as friends and equals. Meanwhile, groups such as The Buzzcocks and Tom Robinson Bandwrote explicitly about queerness.

Relax

Frankie Goes to Holliwood

The early 80s saw punk explode into numerous musical movements. Synthpop, a marriage of the experimental electronica of Kraftwerk and the melodic sensibilities of New Wave, offered a new perspective of what being a man in a band could mean. Gone were the aggressive guitars and drumkits, and in came lush atmospheric synths and the disco beats of drum machines.

Synthpop and the overlapping New Romantic movement once again saw men turning to androgyny as a fashion statement, but they also celebrated sensitivity and courted homoerotica. When Frankie Goes to Hollywood hit the number 1 spot with the track Relax in 1983, they caused controversy, with the BBC and other major stations banning the record due to its suggestive lyrics and the band’s gay imagary. But the song’s, and the band’s, continuing success proved that the genie would not go back in the bottle. The record-buying public was happy to embrace the overt sexuality of these male pop stars.

The synthpop duo Erasure also became a household name in the late 80s, with the openly gay singer Andy Bell penning songs about relationships and emotions that could resonate universally. The band’s signature track, Respect, like many of their hits, was written in a gender neutral way. It didn’t matter about the genders of the lovers involved, what mattered was respect.

Comes as you are

Kurt Cobain

Punk rock saw its second coming in the grunge movement of the early 90s. Inspired in part by mixed-gender DIY movements in the U.K., the early grunge scene retained much of the progressive politics of punk while adopting the aggressive tones of heavy metal.

Kurt Cobain, perhaps the most recognisable figure of the scene, openly supported LGBTQ+ rights and was explicit in his distaste for any form of bigotry, including misogyny. He was also vocal about his hatred of sexual violence, as shown in the songs Rape Me, from In Utero and Polly from Nevermind.

Grunge still suffered from machismo, yet lyrically, Cobain offered a sensitivity and vulnerability that had been missing from heavy rock. He sang openly about despair, loneliness and self-doubt.But Cobain suffered chronic pain, depression and drug addiction, and in 1994 he committed suicide. In his suicide note, he talked about how he was unable to meet the expectations of fame. Cobain’s influence on alternative rock lives on, with many artists carrying on his confessional and vulnerable lyrical style — yet his tragic death is a reminder that for many men, success is meaningless when their own mental health issues are ignored.

The kids are alright

We now live in a time when gender norms are being challenged more than ever before. More famous figures, from pop stars to politicians, are openly gay or bisexual, and owning an identity other than the one assigned to you at birth is slowly, in some areas, becoming more accepted. Artists like Lil Nas X, Harry Styles, Perfume Genius, and Sam Smith offer contrasting views of what being born a man can look like.

Lil Nas X

And yet we are still surrounded by toxic masculinity. Sexual assault, workplace bullying, and street violence are all serious problems. Subcultures such as incels turn sexual entitlement into dangerous political views, radicalising young males and carrying out acts of terrorism. Trans issues have been highly politicised, with transwomen and drag artists being accused of pedophilia, a frightening reminder of the gay moral panics of the 70s and 80s.

So while we celebrate male artists who in some way challenged dominant toxic masculinity, it’s important to remember that behaviours and attitudes traditionally assigned to men — such as a need for emotional, physical, and financial dominance, as well as sexual aggression and other forms of violence — are not set in stone for any of us. Masculinity, like femininity, is not essential but something constructed over generations. Just like Little Richard or David Bowie showed us, masculinity is a costume that you can change to suit who you want to be.